When Turkey stops living for 60 seconds

Passports remind me of spy movies. Spies always have a few of them for each nationality. My passport is Bordeaux red and says “Europese Unie – Koninkrijk der Nederlanden”. When you open the leathery cover with two golden lions there is a picture of 20-year old Frank, looking like he just took a mugshot for prison. Thanks to easy EU travels, my stamp collection is limited to two US stamps, and one Turkish, dating to the 10th of September 2014. That’s the date I also became a ‘spy’. A ‘spy’ on Turkish culture.

Exactly two months later, on the 10th of November, I wake up with a mission on my mind: Being at Dolmabahce palace at exactly 9:05. Today Turkey remembers the death of its founding father, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

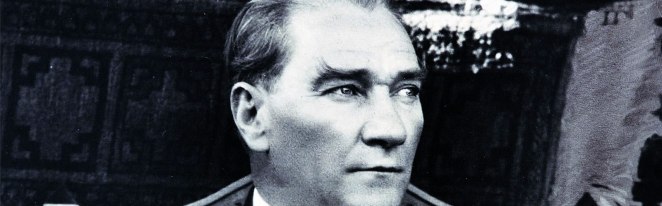

The man who changed everything, and whose pictures can be found in every living room. He established the republic of Turkey, secularized the entire country, and changed the alphabet from Arabic to Latin.

It’s 8:40 and as I’m about to leave the house I get one of those mini-heart attacks: I can’t find my passport.

9:05 is the time Atatürk passed away. That’s why I wanted to be at Dolmabahce at this exact moment, because the sirens go off and everything in Istanbul comes to a halt for one minute. Since I had to search for my passport I am late and witness this spectacle on a street corner. Still, it is fascinating to see how taxis stop and people come to a halt in the middle of crossing the street.

Down on the main road, traffic has stopped as well, but this is because there are simply too many cars. Further on, a similar ‘traffic jam’ takes place: literally thousands of people are standing in front of the palace, patiently waiting to enter the room where Kemal Atatürk took his last breath (and probably his last sip: people say his only mistake was drinking too much).

I believe it’s important to note that this should not be a criticism of Turkish culture. Rather, these are observations of someone who is in a foreign country and has no clue what is going on. Like always, such new experiences are ‘weird’. And like always, such experiences broaden your horizon.

I have been told that the educated people would attend this happening. Yet somehow I find it hard to combine the idea of the educated masses with such glorification of one person. Hans, a German friend, reminds me that this has taken on the proportions of a religion. And religion after all, is practiced by young and old, poor and rich, dumb and intelligent.

As far as I can tell, all of these different groups are indeed present. No matter if they wear a suit, jeans, headscarf or dress, what characterizes these people is their love for this man; a love that has been reinforced by Erdoğan’s game of power. The more Erdoğan tries to establish himself as Turkey’s boss, the more his opponents draw back to their own symbol of peace and hope.

This is a good day for kids, because school trips are always fun, and today they get to visit the palace as well. Hans tells me that until two years ago the following was recited every day:

I am a Turk, honest and hardworking. My principle is to protect the younger to respect the elder, to love my homeland and my nation more than myself. My ideal is to rise, to progress.

Oh Great Atatürk ! On the path that you have paved, I swear to walk incessantly toward the aims that you have set.

My existence shall be dedicated to the Turkish existence. How happy is the one who says “I am a Turk!”.

Atatürk died in 1938. The rise of such nationalism is actually quite ‘normal’ when you think of what happened in Germany that point in time…

Of course today such a hymn would be unthinkable in Germany, despite it’s positive encouragement to be hard-working and honest. Although the Dutch don’t have a national trauma like the Germans, I think they are also more reserved about their country (most of the year).

There is a Dutch saying: be normal, than you’re crazy enough already (Dutch houses in Amsterdam, whether filthy rich or dirt poor, all look the same on the outside). When no one stands out, no one can be adored. But hey, here swings in the Dutch national pride: I’m proud of my country not being proud. Not as proud as the French or English anyway.

Right, I am Dutch. Mostly. But then again, how can I prove this without my passport?

As I make my way to find this valuable document I encounter Istanbul’s street sellers, like usual. They must have some underground storage room, because they can instantly switch their goods. One minute they’re selling water and the second it rains they’re ready to assist you with umbrellas. Today their collection features Turkish flags and Atatürk pictures.

As I make my way to find this valuable document I encounter Istanbul’s street sellers, like usual. They must have some underground storage room, because they can instantly switch their goods. One minute they’re selling water and the second it rains they’re ready to assist you with umbrellas. Today their collection features Turkish flags and Atatürk pictures.

Another ‘different’ aspect of Turkey is that you have to register your phone and pay a fee in order to use it. I underwent this yesterday, and of course you need your passport for this annoying procedure, which is why I put all my hopes on finding it at the Turkcell shop.

Never had it felt so good to catch a glimpse of this leathery, brown document that makes me a Dutch citizen.

Turkey is great, and its citizens have a lot of reasons to be proud of it. Funny enough, being here has also made me a proud Dutchman (or Western European), as I’m becoming more aware of what characterizes the Dutch (or Western Europeans) by living in such a different cultural environment.

Nationalism is a funny thing, and certainly has its pro’s and con’s. By learning more about each other’s cultures, I hope we can use our differences more as celebration than as barrier.