What I've learned in Asia's biggest slum

In an area half of central park, more than one million people survive in Asia's biggest slum. I had seen a lot of poverty in India, and I tried to prepare for the worst. But the slum of Dharavi surprised me.

Our guide Raj takes me and Paul, an Australian pilot, up a walking bridge to cross the rail tracks. On the other side we enter into a different world. Raj wears trendy jeans and Allstars, and doesn't lack the typical city-guide-for-trendy-young-people-charisma. He also grew up in this slum.

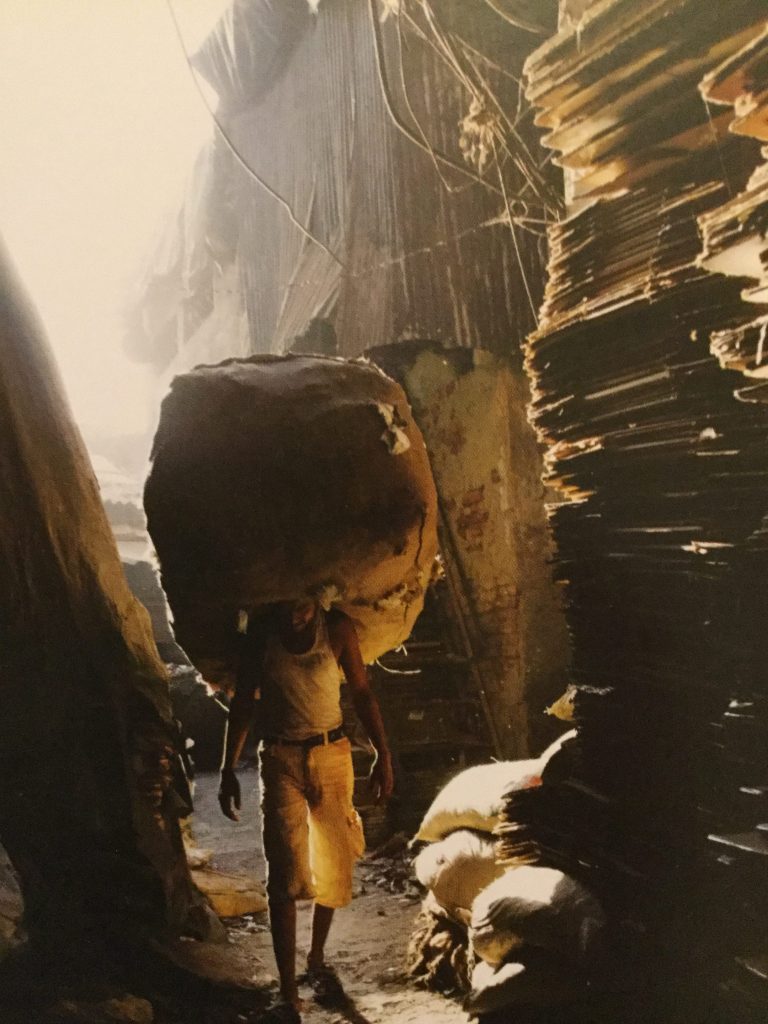

We wander down a wide and bustling road full of trash, goats, and people. I definitely feel weird about this; I'm a tourist in a slum. We take a left turn turn and enter a narrow alley with towers of plastic waste. A young boy sorts empty oil canisters by colour, and around the corner two men are unwinding and dissembling VHS cassettes. This is the area where plastic is recycled, melted, and formed into tiny pallets. I wonder whether my plastic waste in the Netherlands ever reaches this precision of recycling. We climb a ladder onto the second story rooftop to get a 360° view of the area. Raj explains that the roofs are used to dry and store the plastic and animal skins.

In a dark little hut, a big fellow with a huge glove is melting aluminium. The red glow of the room heats my cheeks and my nose is filled with stinging smoke. A few sun rays shine through a small crack in the roof and illuminate the million specks of dust. On the walls someone wrote "Safety first".

Raj takes us through more narrow pathways, all the while greeting people and joking with the kids. Although we get some stares, it's as if people are used to seeing foreigners here. Something else tells me this is probably true: It seems like the first thing 2-years olds learn is how to say "Hiiiiii, how are you?". But it's genuine, and their happiness melts my heart. Kids are simply the best.

Next are the residential areas; "Watch your head". The next alley is barely wider than my shoulders and resembles more of a tunnel. All kinds of cables are dangling at the height of my neck. This is the way to their homes. We wiggle through the labyrinth, a girl gives us high fives and at a doorstep, and a smartphone illuminates the face of a young boy. At the other end, we emerge back into the sunlight, where a small courtyard stretches out in front of us. Dozens of laughing kids are playing in the dusty fields. Two boys are looking down through the cracked metal rooftop of a school building. I think to myself how much fun they're having compared to the overprotected kids back home, who only stare at screens all day.

People seem quite happy here, but one of the longterm problems must be health. There is another problem, something also to be found in the West. Since the parents work all day, the children miss parental guidance and attention.

Here Raj shows us the leather industry and he takes us into a shop and I can hardly believe what I see. We enter through a glass door into the chilled air of an airconditioned and very tidy shop. There are lots of designer-looking bags and leather jackets. Some of the gold-decorated bags wouldn't look misplaced at a Dolce & Gabbana store.

Now we're heading towards a small school. While there is government funded education, the quality is low, which is why people try to send their children to better schools. This is definitely inspiring: These men and women work to send their kids to school. I can't help but compare it to the often pathetic reasons we Westernes work hard. Buying a bigger car. A new phone. A longer vacation.

In one of the classrooms, a group of women is learning English. This is one of the classes run by the organisation Raj works for, and where they use the money they receive from tourists like me. The other two classes they teach are computer and soft skills, targeted at helping them land a nice job. The only reason I could justify to take part in this sort of 'poverty-tourism' is the motive behind the tour. The organisation invests 80% of its profits back into the community, and as far as I can tell, the money is well spent.

I would have loved to take pictures of the kids, the workers, the houses, but they have a strict no photography rule. The movie 'Slumdog millionaire' was shot here and because it only showed the worst side, people didn't like it. "It was like that only in the 80s, those times are long gone," Raj tells us, "so now people are very skeptical of people taking pictures, because they think it will be negative." I understand their concern, and when I see two white women with a 'freelance' guide taking pictures it does seem wrong. I would have loved to tell the positive sides of Dharavi, so I bought three postcards to do that. Each of these pictures represents a surprising new insight, and something inspirational.

1 Yes, the living conditions are crazy, but it has improved a lot. There is electricity and running water, the people are registered citizens, and the gang violence has vanished (albeit only due to brutal police force in the 90s).

2 People come here to work. And work they do, all to send their children to better schools. A lot of the world's cheap products are produced in places like this, and it illustrates how complicated issues like child labour are. Yes, we don't want people to work 14 hour days in toxic working conditions. But we also don't want to take away their opportunity and pride of their shot a bit more prosperity.

3 Most inspiring is that a slum like Dharavi has something that European and American cities lack: A sense of community. People yearn for better living conditions, but they are happy here, because they have each other. Community is one of the primary sources of happiness. The children definitely seem happy, perhaps happier than the children of the many divorced workaholics from New York to Amsterdam.

My experience in Dharavi has definitely changed my views of a slum in India. I can see a lot of good things, but I also want to be careful not to romanticise it. A slum after all, is still a slum.

[…] Now I’m ready for next part: Dharavi Slum Tour […]